Analysis

Initial Analysis of Words and Language: Understanding more about 1918 Amherst Vernacular Towards the Spanish Flu

A web-based program called Voyant was used to analyze the text document and to produce information about the composition of each article. It highlighted more about the language used to describe the epidemic. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the program extracted the top five terms from the document and counted the number of times these terms appeared; it also broke the document into ten segments and mapped how frequently various terms were used in the ten segments of the text.

Looking at Figures 2 and 3, the top five words in the document are: “amherst,” “cases,” “college,” “epidemic,” and “influenza.” The word “cases” peaks the highest in segment 10 of the document because during early December, a Student article described the number of cases at the College during two phases of the epidemic (“Flu” 1). The word “college” appears more in the beginning of the document than at the end; it might be that many more of the articles from September and early October address the community as a whole, whereas the articles later on are more specific to certain student organizations and groups. Interestingly, the words “cases,” “college,” “epidemic,” and “influenza” all peak at segment 5 of the document; the words “epidemic,” “cases,” and “influenza” all peak at segment 10 of the document as both segment 5 and segment 10 of the document represent articles written in the midst of an influx of cases or articles that describe a recent peak in cases. Additionally, authors seem to use both “epidemic” and “influenza” interchangeably to refer to the crisis at hand; while there are more instances of the use of the word “influenza,” there are almost as many uses of the word “epidemic.” It is thus clear that “influenza” and “epidemic” were the two most popular ways to address the crisis during the fall of 2018.

Secondary Analysis of Words and Language: Measuring Amherst College’s Response to the Epidemic

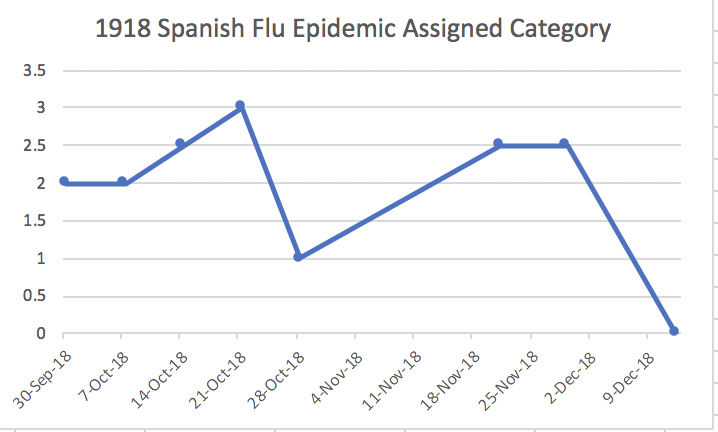

Further analysis on the Amherst community’s response was conducted with resources from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Excel, and the text document. The CDC’s Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework categorizes pandemics by how transmissible the illness is and how likely it is to cause infection. For a category 2 or 3 pandemic, the CDC recommends the “voluntary isolation of ill at home”; institutions and citizens should consider the “voluntary quarantine of household members in homes with ill persons” and “child social distancing for maximum of 4 weeks” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). The 1918 Spanish Flu is a category 5 pandemic, meaning that 2% of total cases reported are deaths and that the pandemic is quite severe (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Examining the language describing the epidemic in my text document proved crucial to ultimately understanding how the Amherst community responded to the epidemic. As shown in Figure 4, categories were assigned to each issue of the newspaper based on how the authors and community members talked about the pandemic and what measures the author defined as being taken at the time. The purpose of such analysis was to understand whether or not the College took the pandemic seriously and treated it as a category 5 pandemic.

| Amherst Student Newspaper Date | Appointed Category | Language of Text |

| October 14, 1918 | 2/3 | “Freshman Dies but Others are Recovering–Only Two of Twenty Cases still serious,” “only fatality thus far,” “only one or two…reported as really serious,” “climax has not yet been reached,” “on the decline,” “suspending all classes and chapel services indefinitely,” “open air,” “required to report,” “rigid rules of sanitation,” “a menace to the health of the college” (1) |

What can we conclude about their response?

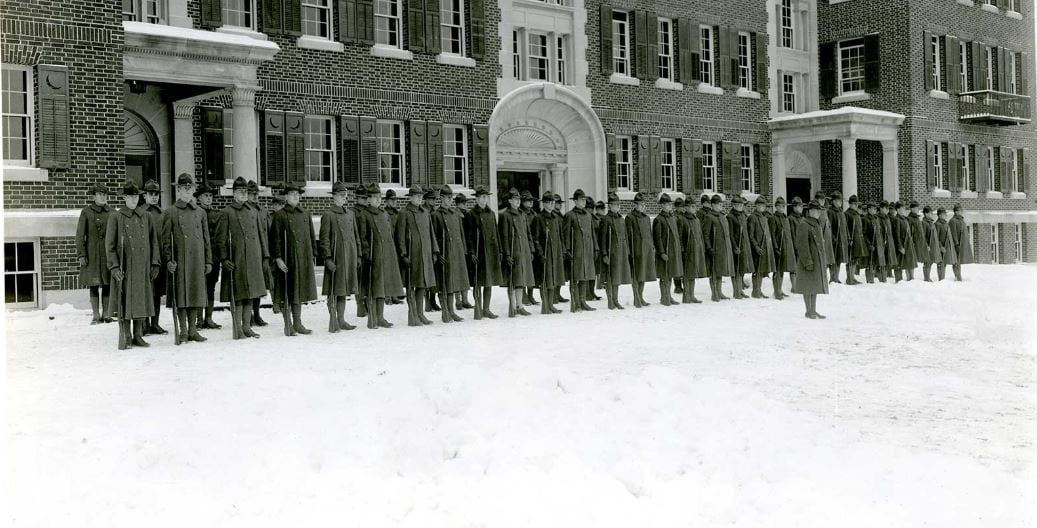

It is clear from both Figures 4 and 5, the hiring of top physicians and medical personnel, and appointing of students to help regulate illness in the student community that Amherst College tried to act in a calm, controlled way during the 1918 epidemic. As the College did not have many deaths or cases, it seems as if they dealt with the epidemic well; however, an analysis of the language used in various Amherst Student Newspaper articles seems to challenge the notion that Amherst took strong and persistent action against the spread. These articles seemingly demonstrate that the College did not treat the outbreak as a category 5 pandemic as shown in Figure 5. There could have been more action to combat the epidemic; however, healthcare regulations and attitudes towards tragedy, war, and disease were extremely different in 1918. Amherst’s response thus probably reflected the viewpoints at the time and while their response is quite inadequate, it is important to look at the epidemic through the lens of a community riddled by war and under the guise of a very different healthcare system. These contextual frames of reference are crucial to understanding why the 1918 Amherst community’s response fell short of our own current response.

You must be logged in to post a comment.